Act II: The Second Voyage

Expedition (1772–1775): Two ships (Resolution and Adventure), 193 men

Charge (by the Royal Society and the British Admiralty): To search for the Southern Continent and to test a version of the John Harrison chronometer for longitude determinations

Accomplishments: Sailed further south than any previous mariner (71°10′ S) and discovered South Georgia Island and the South Sandwich Islands

[Click on the images below for high resolution versions.]

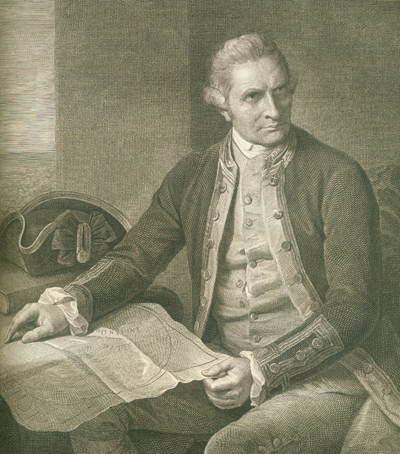

Portrait of Captain James Cook. Engraving by J. K. Sherwin, after a painting by Nathaniel Dance, 1776. From the John Wild Autograph Collection. [Manuscripts Division]

Absent three years, Cook had arrived home in 1771 to learn from this wife that his youngest son, Joseph, had died shortly after he had embarked and that his only daughter, Elizabeth, had succumbed just recently while he was heading home from the Cape; but his oldest sons, James and Nathaniel (aged eight and seven), fortunately were well. The circumnavigator busied himself with preparing a final version of his journal, revising and copying his charts, and writing letters and recommendations for promotion. His fame and accomplishments were quickly overshadowed by Banks and his dizzying publicity schedule—the botanist was already thinking of a second, more grand expedition.

Within a month (August 1771), Cook had been promoted to captain and asked to take another voyage to the Pacific in search of that elusive Southern Continent, an idea still kept on life-support by its champion Dalrymple and others in positions of authority. Accepting the offer without hesitation, Cook decided that he would operate from two fixed bases where sources of food, wood, and water were reliable: Matavai Bay (Tahiti) and Queen Charlotte Sound (New Zealand). It would be a voyage of vast ocean sweeps, circling the globe, this time, in an easterly direction. Once again, the Royal Society and the British Navy were the support teams. Two ships were secured, the Resolution for Captain Cook and the Adventure for Captain Tobias Furneaux (1735–1781), who had served under Wallis.

Book:

Cook, James. A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World: Performed in His Majesty’s Ships the Resolution and Adventure, in the Years 1772, 1773, 1774 and 1775. 1st ed. 2 vols. London, 1777. [Rare Books Division]

In the published narrative of this second voyage, Cook was determined to prevent the kind of editorial license that John Hawkesworth had enjoyed with his first. Despite the literary limitations acknowledged here, he assumed full authorial control:

I shall therefore conclude this introductory discourse with desiring the reader to excuse the inaccuracies of style, which doubtless he will frequently meet with in the following narrative; and that, when such occur, he will recollect that it is the production of a man, who has not had the advantage of much school education, but who has been constantly at sea from his youth; and though, with the assistance of a few good friends, he has passed through all the stations belonging to a seaman, from an apprentice boy in the coal trade, to a Post Captain in the Royal Navy, he has had no opportunity of cultivating letters. After this account of myself, the Public must not expect from me the elegance of a fine writer, or the plausibility of a professed book-maker; but will, I hope, consider me as a plain man, zealously exerting himself in the service of his Country, and determining to give the best account he is able of his proceedings. [From Cook’s introduction to vol. 1, p. xxxvi, dated July 7, 1776]

In fact, in these volumes Cook proves to be a very good, effective, and interesting writer.

Having hoped to depart in March, Cook finally set sail from Plymouth on July 13, 1772. The delay was caused by Banks, who, planning to join and make a more robust expedition, had gotten the Admiralty’s approval for its shipyard to make extensive repairs to Resolution, expanding its accommodations for his larger staff by raising its “waist” and building a new deck. In its upgraded condition, however, the ship proved top-heavy and unseaworthy, and the Royal Navy immediately engaged two hundred carpenters and shipwrights to demolish the addition. Furious, Banks removed himself and retinue from the project, and the drama ended. Among the personnel on this second voyage were artist William Hodges (1744–1797); young George Vancouver (1757–1798), the future surveyor of North America’s northwest coast; and two Royal Society astronomers who were accompanying a replica of John Harrison’s famous H4 chronometer made by Larcum Kendall, which Cook would be testing to determine longitude by comparing its results with those obtained by lunar observations, his more familiar method.

After stops in Madeira (reached July 29) for wine and the Cape of Good Hope (October 30) to refresh and obtain additional supplies, the real mission began. For the four-month period from November 22, 1772, when Resolution and Adventure departed from South Africa, until March 26, 1773, when Cook’s ship entered Dusky Bay (New Zealand), more than ten thousand miles of sea were traversed, out of sight of land, in fog, around ice fields, dodging icebergs, even dipping at one point below 67° S, just seventy-five miles from undiscovered Antarctica. Cook was scrupulous about maintaining the cleanliness of his ship, ordered the crew to frequently change and wash their clothes, and imposed his sense of a healthy anti-scorbutic diet—resistance was dealt with harshly. Both captains realized the likelihood of dangerous weather conditions separating them and thus planned a rendezvous in Queen Charlotte Sound (New Zealand); poor visibility in February hastened the inevitable. Furneaux, as Cook later learned, finally sailed off and explored the eastern coast of Tasmania before heading to New Zealand; on the way Cook took time to explore the remote and magnificent Dusky Bay that he had passed by on his last trip. (See Cook’s map of Dusky Bay, which is located on the southwest corner of New Zealand’s southern island.)

“The Ice Islands, Seen the 9th of Jan.ry 1773.” [vol. 1, plate XXX]

In the afternoon we passed more ice islands than we had seen for several days. Indeed they were now so familiar to us, that they were often passed unnoticed; but more generally unseen on account of the thick weather. At nine o’clock in the evening, we came to one, which had a quantity of loose ice about it. As the wind was moderate, and the weather tolerably fair, we shortened sail, and stood on and off, with a view of taking some on board on the return of light. But, at four o’clock in the morning, finding ourselves to the leeward of this ice, we bore down to an island to leeward of us; there being about it some loose ice, part of which we saw break off. There we brought to; hoisted out three boats; and, in about five or six hours, took up as much ice as yielded fifteen tons of good fresh water. The pieces we took up were hard, and solid as a rock; some of them were so large, that we were obliged to break them with pick-axes, before they could be taken into the boats. The salt water which adhered to the ice, was so trifling as not to be tasted, and, after it had lain on deck a short time, entirely drained off; and the water which the ice yielded, was perfectly sweet and well-tasted. [vol. 1, p. 37]

Sailing Conditions below the Antarctic Circle

(66°33′39″ S)

Friday 24th [December 1773]. . . . Lat. in South 67° 19′. . . . Our ropes were like wires, Sails like board or plates of Metal and Shivers froze fast in the blocks so that it required our utmost effort to get a Top-sail down and up; the cold so intense as hardly to be endured, the whole Sea in a manner covered with ice, a hard gale and a thick fog: under all these unfavourable circumstances it was natural for me to think of returning more to the North, seeing there was no probability of finding land here nor a possibility of get[ting] farther to the South and to have proceeded to the East in this Latitude would not have been prudent as well on account of the ice as the vast space of Sea we must have left to the north unexplored, a space of 24° of Latitude in which a large track of land might lie, this point could only be determined by making a stretch to the North. [Journals, p. 325]

Cook, James, 1728–1779. “Sketch of Dusky Bay in New Zeeland, 1773.” Copperplate map, with added color, 20.2 × 37.6 cm. Plate no. XIII from vol. 1 of Cook’s A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World . . . (London, 1777). [Historic Maps Collection]

For six weeks, Cook’s crew (and their ship) benefited from recuperative activities—smoking fish, brewing beer, repairing sails and other damage, shooting fowl and seals, gathering wood and water—and exploring the complex fjord. Cook and his officers made contact with a Maori family, and they exchanged visits to each other’s “home.” Resolution and Adventure were reunited in Ship Cove in Queen Charlotte Sound on May 18. Cook, however, was not pleased with Furneaux’s lack of discipline and dietary supervision: many of his crew were afflicted with scurvy, which would be a continuing, serious problem in the Adventure despite Cook’s instructions to the captain on how to deal with it (sauerkraut, cabbage, wild celery and scurvy grass, etc.) For the rest of the Southern Ocean’s winter season, the ships scoured the Pacific between New Zealand and South America, searching for a Southern Continent, before arriving in Tahiti in August, where civil war had altered the politics and personnel since Cook’s previous visit in 1769.

But the constant thieving had not changed. Finding new and missing faces, Cook maintained generally good relations with the islanders. Leaving in September, the expedition, in its run back to New Zealand, began tackling the voyage’s other, unacknowledged purpose of verifying and revising discoveries, both of Cook and earlier navigators—here, through the Society Islands and the Friendly Islands (Tonga). The men noted that the Tongans seemed more advanced in their cultivation of crops and construction of boats, among other things, than their Tahitian counterparts. From Huahine, one of the Society Islands, Furneaux picked up a young priest, Omai, who begged to be taken to see “Britannia.” (For more on Omai, see the related illustration and caption.)

“The Island of Otaheite Bearing S. E. Distant One League” [vol. 1, plate LIII]

Soon after our arrival at Otaheite, we were informed that a [Spanish] ship, about the size of the Resolution, had been in at Owhaiurua harbor near the S. E. end of the island, where she remained about three weeks; and had been gone about three months before we arrived. . . . The Otaheiteans complained of a disease communicated to them by the people in this ship, which they said affected the head, throat, and stomach, and at length killed them. They seemed to dread it much, and were continually inquiring if we had it. . . . Were it not for this assertion of the natives, and none of Captain Wallis’s people being affected with the venereal disease, either while they were at Otaheite, or after they left it, I should have concluded that, long before the islanders were visited by Europeans, this, or some disease which is a near kin to it, had existed among them. [vol. 1, pp. 181–82]

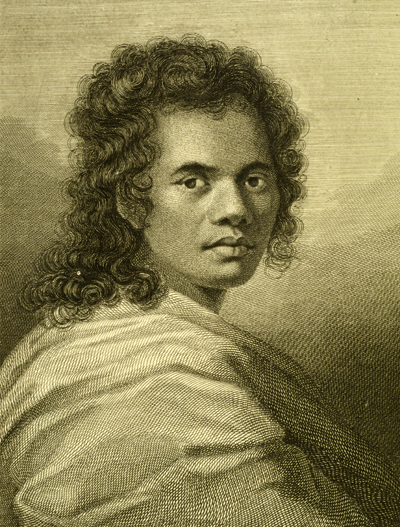

“Omai” [vol.1, plate LVII]

Before we quitted this island [Huahine] Captain Furneaux agreed to receive on board his ship a young man named Omai, a native of Ulietea, where he had some property, of which he had been dispossessed by the people of Bolabola. I at first rather wondered that Captain Furneaux would encumber himself with this man, who, in my opinion, was not a proper sample of the inhabitants of these happy islands, not having any advantage of birth, or acquired rank; nor being eminent in shape, figure, or complexion. . . . I have, however, since my arrival in England, been convinced of my error: for excepting his complexion . . . I much doubt whether any other of the natives would have given more general satisfaction by his behaviour among us. Omai has most certainly a very good understanding, quick parts, and honest principles; he has a natural good behaviour, which rendered him acceptable to the best company, and a proper degree of pride, which taught him to avoid the society of persons of inferior rank. He has passions of the same kind as other young men, but has judgment enough not to indulge them in an improper excess. . . . Soon after his arrival in London, the Earl of Sandwich, the first Lord of the Admiralty, introduced him to his Majesty at Kew, when he met with a most gracious reception, and imbibed the strongest impression of duty and gratitude to that great and amiable prince . . . . It is to be observed, that though Omai lived in the midst of amusements during his residence in England, his return to his native country was always in his thoughts. . . . He embarked with me in the Resolution, when she was fitted out for another voyage [Cook’s third voyage], loaded with presents from his several friends, and full of gratitude for the kind reception and treatment he had experienced among us. [vol. 1, pp. 169–71]

At the end of October in a gale off the east coast of New Zealand, the two ships were separated again—this time for good. Unlike Cook, Furneaux was unable to get back to Queen Charlotte Sound for a month, during which time Resolution had been repaired, sailing eastward on November 25, out of Cook Strait and south for Antarctic exploration. (They had missed each other by a week.) Furneaux found a letter Cook had left for him in Ship Cove—“Look Underneath” had been carved on a stump, with the note in a bottle buried at the base—explaining his strategy through March and essentially freeing his partner to make his own plans. That was easily decided: Furneaux and his men wanted to go home. However, in gathering wild greens in nearby Grass Cove, all ten crew members of a cutter were savagely attacked and killed by Maori Indians, and their bodies were cannibalized. A search party found the horrific evidence the next day: it was totally inexplicable. Furneaux restrained his desire for revenge, and Adventure set sail immediately. Via Cape Horn, they reached Table Bay in Cape Town on March 19 and were back in England (with Omai) on July 12, 1774.

Unaware of Furneaux’s experience, Cook rigorously pursued the high latitudes of the southern Pacific Ocean through the summer season (November–February), crossing the Antarctic Circle several times and reaching a record 71°10′ S at the end of January. Stymied by pack ice and severe cold, barely escaping wrecking on a huge iceberg, Cook concluded there could be no habitable Southern Continent, only a frozen land nearer the pole. Still, like him, none of his men or officers wanted to go home, so he adjusted course to the north and arrived at Easter Island on March 12; during the passage, Cook had been alarmingly ill for a week.

For the next seven months, Resolution and its crew enjoyed the tropics, while continuing the necessary exploring and charting activities, sometimes revisiting islands last touched by Europeans two hundred years earlier. (Where Cook was known from his previous visits, there were many joyful, but teary-eyed, welcomes and departures.) Among the stops were the Marquesas, Tahiti again, other Society Islands, the Friendly Islands, the New Hebrides (named by Cook but part of Vanuatu), and other islands of the Polynesian and Melanesian archipelagoes; they also made the first European discovery of New Caledonia. On October 18, 1774, Cook was back in Ship Cove in Queen Charlotte Sound and found his bottle and message gone; initially, the Maori acted very suspiciously (for obvious reasons), but soon resumed friendly relations. Restocked with fresh fruit, vegetables, fish, fowl, and other meat, Resolution departed on November 10.

“Possession Bay in the Island of South Georgia” [vol. 2, plate XXXIV]

[Tuesday, January 17, 1775] As I had come to a resolution not to bring the ship in, I did not think it worth my while to go and examine these places; for it did not seem probable that any one would ever be benefited by the discovery. I landed in three different places, displayed our colours, and took possession of the country in his Majesty’s name, under a discharge of small arms. . . . The head of the bay, as well as two places on each side, was terminated by perpendicular ice-cliffs of considerable height. Pieces were continually breaking off, and floating out to sea; and a great fall happened while we were in the bay, which made a noise like a cannon. The inner parts of the country were not less savage and horrible. [vol. 2, p. 213]

Unlike Furneaux, Cook did not rush back to England, though he had the wind with him. He took Resolution down to 55° and kept that “tolerable” parallel going east to Cape Horn for five weeks, covering on one day, under a steady gale, a record 183 miles. They celebrated Christmas, protected in a cove within what Cook named Christmas Sound (still used today) on the western side of Tierra del Fuego, enjoying dozens of geese they had shot. After passing Cape Horn, Cook explored the vast South Atlantic, west of where he had started when leaving Cape Town two years before, discovering and claiming the “savage” land of South Georgia (January 17) and the South Sandwich Islands and dipping down to the 60° S level. Icebergs and ice fields and thick fog and cold: one little mistake could bring a sudden, disastrous end to the whole expedition and loss of all the voyage’s charts and acquired knowledge. Enough was enough—it was on to Cape Town, which Resolution reached on March 22. The Harrison/Kendall watch had proved accurate within 18′, or less than one-third of a degree.

Cook received news of the Adventure and had his first look at the “official” published narrative of Endeavour’s voyage, written by the English journalist John Hawkesworth. It was very distressing to read how he had misused Cook’s journal and featured Banks so prominently. Voyaging back to England, they stopped at St. Helena, made a detour to locate the Portuguese outpost island of Fernando de Noronha near Brazil (Cook, ever the opportunist), and reached the southern coast of England the next month, anchoring at Spithead on July 30, 1775. Cook had lost four men, one by sickness (tuberculosis) and probably the others from drunken accidents; he was most proud of that record and had high praise for his officers and men in his dispatch to London. The extraordinary voyage ended, essentially nailing shut and burying the proverbial Southern Continent coffin.

1638: Hondius, Hendrik, 1597–1651. “Polus Antarcticus.” Copperplate map, with added color, 44 cm. in diameter on sheet 44 × 50 cm. From J. Jansson and H. Hondius’s Atlas novus (Amsterdam, 1638). Reference: Tooley, Australia 726 (state 1) [Historic Maps Collection].

Shows the concept of an undetermined but vast Southern Continent, or Terra Australis.

1757: Buache, Philippe, 1700–1773. “Carte des Terres Australes. . . .” Copperplate map, with added color, 23 cm. in diameter on sheet 24 × 31 cm. Probably from Guillaume de L’Isle’s Cartes et tables de la géographie physique ou naturelle . . . (Paris, 1757) [Historic Maps Collection].

First published in 1739, dated 1754 but bearing 1756 notes, this map is a good representation of the state of the myth of the Southern Continent in the decades before Cook’s second voyage.

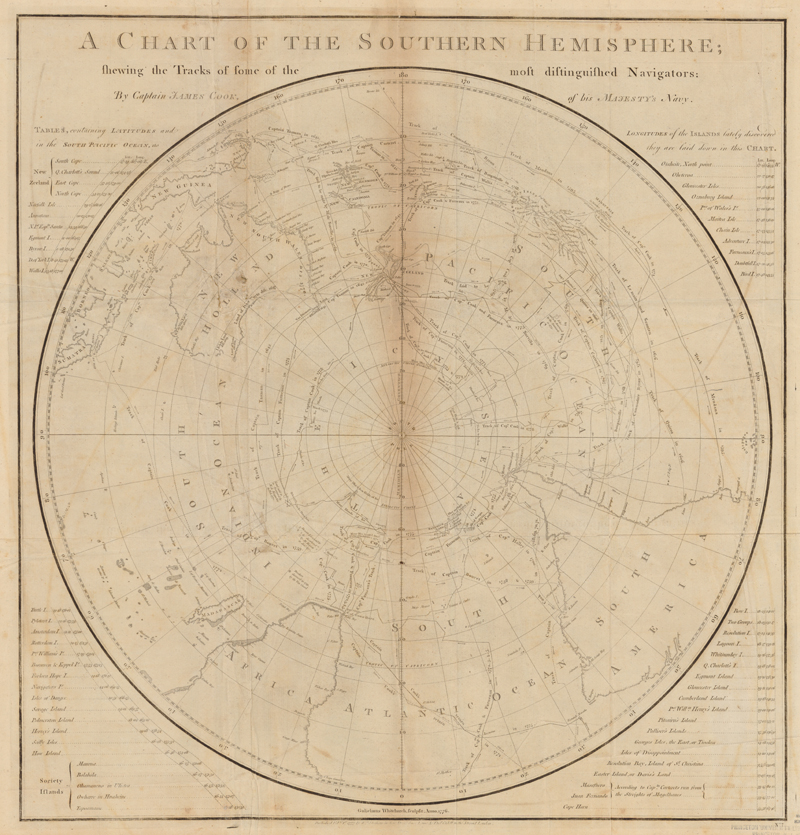

1777: Cook, James, 1728–1779. “A Chart of the Southern Hemisphere.” Copperplate map, 50 cm. in diameter on sheet 56 × 54 cm. From vol. 1 of Cook’s A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World . . . (London, 1777) [Historic Maps Collection].

The myth of a habitable Southern Continent—exploded.

Cook’s Reflections on His Second Voyage

|